Financial derivatives: option, futures, swap

Derivatives are the instruments which include security derived from a debt instrument share, loan, risk instrument or contract for differences of any other form of security and a contract that derives its value from the price/index of prices of underlying securities. In finance field, a derivative is a contract that derives its value from the performance of an underlying entity. This underlying entity can be an asset, index, or interest rate, and is often called the "underlying". Financial derivatives are effective financial instruments that are related to a specific financial indicator or commodity, and through which specific financial risks can be merchandised in financial markets in their own right. Transactions in financial derivatives should be treated as separate transactions instead of integral parts of the value of underlying transactions to which they may be associated. The value of a financial derivative derives from the price of an underlying item, such as an asset or index. Dissimilar to debt instruments, no principal amount is advanced to be repaid and no investment income accrues. Financial derivatives are used for various purposes such as risk management, hedging, arbitrage between markets, and speculation (Ali Hirsa, 2013).

Derivatives markets are successful organisations because they make financial markets more efficient. This generally means that borrowing and lending can occur at lower cost than would otherwise be the case because derivatives decrease transaction costs.

Financial derivatives allows parties to trade specific financial risks (such as interest rate risk, currency, equity and commodity price risk, and credit risk, etc.) to other entities who are more willing, or better suited, to take or manage these risks typically, but not always, without trading in a principal asset or product. The risk exemplified in a derivatives contract can be traded either by trading the contract itself, such as with options, or by developing a new contract which embodies risk characteristics that match, in a countervailing manner, those of the existing contract owned. This latter is termed offset ability, and occurs in forward markets. Offset ability means that it will often be possible to eradicate the risk associated with the derivative by creating a new, but "reverse", contract that has features that countervail the risk of the first derivative. Buying the new derivative is the functional equivalent of selling the first derivative, as the result is the removal of risk. The ability to replace the risk on the market is therefore considered the equivalent of tradability in representing value. The expenditure that would be required to replace the existing derivative contract represents its value, actual offsetting is not required to demonstrate value.

Derivatives can be used for several reasons such as insuring against price movements (hedging), increasing exposure to price movements for speculation or getting access to otherwise hard-to-trade assets or markets. Some common derivatives include forwards, futures, options, swaps, and variations of these such as synthetic collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps. Most derivatives are merchandized over-the-counter (off-exchange) or on an exchange such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, while most insurance contracts have developed into a separate industry.

Common financial derivatives (Ali Hirsa, 2013):

- Options: Details follows in subsequent section.

- Forward Contracts: In a Forward Contract, both the seller and the purchaser are indebted to trade a security or other asset at a definite date in the future. The price paid for the security or asset may be agreed upon at the time the contract is entered into or may be determined at delivery. Forward Contracts generally are traded OTC.

- Futures: Details follows in subsequent section.

- Stripped Mortgage-Backed Securities: Stripped Mortgage-Backed Securities, abbreviated as SMBS, are Securities that reallocate the cash flows from the underlying generic MBS collateral into the principal and interest components of the Mortgage-Backed Securities to enhance their attractiveness to different groups of investors. Stripped Mortgage-Backed Securities are introduced by Fannei Mae in 1986. A mortgage pass through security divides the cash flow from underlying pool of mortgages on a pro data basis to the security holders. Stripped Mortgage-Backed Securities is created by altering that distribution of principle and interest from pro data distribution to an unequal distribution. The result is that some of the securities created will have a price/ yield relationship that is different from a price/ yield relationship underlying mortgage pool (Fabozzi, 2002).

- Structured Notes: Structured Notes are debt tools where the principal and/or the interest rate is indexed to dissimilar indicator. For example, a bond whose interest rate is decided by interest rates or the price of a barrel of crude oil would be a Structured Note. Sometimes the two elements of a Structured Note are inversely related, so as the index goes up, the rate of payment (the "coupon rate") goes down. This instrument is called an "Inverse Floater." With leveraging, Structured Notes may change to a greater degree than the underlying index. Therefore, Structured Notes can be tremendously volatile derivative with high risk potential and a need for close monitoring.

- Swaps: Details follows in subsequent section.

- Rights of Use: A type of swap is signified by exchanging capacity on networks using instruments called “indefeasible rights of use”, or IRUs. Companies buying an IRU might book the price as a capital expense, which could be spread over a number of years. But the income from IRUs could be booked as immediate revenue, which would bring an immediate increase to the bottom line. Theoretically, the practice is within the arcane rules that oversee financial derivative accounting methods, but only if the swap transactions are real and entered into for actual business purpose.

- Combined derivative product: Array of derivative products is limited only by the human imagination. Therefore, it is not uncommon for financial derivatives to be merged in various amalgamations to form new derivative products. For example, a company may get benefit to finance operations by issuing debt, the interest rate of which is determined by some unrelated index. The company may have exchanged the liability for interest payments with another party. This product combines a Structured Note with an interest rate Swap.

- Hedge Funds: A hedge fund is a private partnership which has aim to become wealthy investors. It can use policies to lessen risk. But it may also use leverage, which increases the level of risk and the potential rewards. Hedge funds can invest in almost anything anywhere. They can hold stocks, bonds, and government securities in all global markets. They may purchase currencies, derivatives, commodities, and tangible assets. They may leverage their portfolios by borrowing money against their assets, or by borrowing stocks from investment brokers and selling them (shorting). They may also invest in closely held companies.

Reason for using derivatives:

Derivatives are risk-shifting devices. Primarily, they were used to decrease exposure to changes in such factors as weather, foreign exchange rates, interest rates, or stock indexes. Currently, derivatives have been used to separate categories of investment risk that may appeal to different investment strategies used by mutual fund managers, corporate treasurers or pension fund administrators. These investment managers may decide that it is more beneficial to assume a specific "risk" characteristic of a security.

Risk: Since derivatives are risk-shifting devices, it is vital to recognize and understand the risks being assumed, appraise them, and constantly monitor and manage them. Each party to a derivative contract should be able to ascertain all the risks that are being assumed before entering into a derivative contract. Part of the risk identification process is a determination of the monetary exposure of the parties under the terms of the derivative instrument. As money generally is not due until the specified date of performance of the parties' obligations, lack of up-front commitment of cash may obscure the eventual monetary significance of the parties' obligations.

Investors and markets conventionally have considered to commercial rating services for assessment of the credit and investment risk of issuers of debt securities. Some firms issue ratings on a company's securities which reflect an evaluation of the exposure to derivative financial instruments to which it is a party. The solvency of each party to a derivative instrument must be evaluated independently by each counterparty. In a financial derivative, performance of the other party's obligations is dependent on the strength of its balance sheet. Consequently, a complete financial analysis of a proposed counterparty to a derivative instrument is important.

An important aspect in the use of derivatives is the need for constant monitoring and managing of the risks signified by the derivative instruments. For example, the degree of risk which one party was willing to assume initially could change greatly due to intervening and unforeseen events. Each party to the derivative contract should monitor continuously the commitments represented by the derivative product. Financial derivative instruments that have leveraging features demand closer, even daily or hourly monitoring and management.

Options:

Options are agreements between two parties to buy or sell a security at a certain price. They are most often used to trade stock options, but may be used for other investments as well (Kevin, 2014). If an investor purchases the right to buy an asset at a specific price within a given time frame, he has purchased a call option. On the contrary, if he purchases the right to sell an asset at a given price, he has purchased a put option. The seller has the corresponding obligation to fulfil the transaction that is to sell or buy if the buyer (owner) exercises the option. The buyer pays a premium to the seller for this right. An option that conveys to the owner the right to buy something at a certain price is a "call option"; an option that conveys the right of the owner to sell something at a certain price is a "put option". Both are commonly traded, but for transparency, the call option is more frequently discussed. Options valuation is a topic of ongoing research in academic and practical finance. Fundamentally, the value of an option is commonly decomposed into two parts. The first part is the "intrinsic value", described as the difference between the market value of the underlying and the strike price of the given option. The second part is the "time value", which depends on a set of other factors which, through a multivariable, non-linear interrelationship, reflect the discounted expected value of that difference at expiration.

Although options valuation has been done since the 19th century, the modern approach is based on the Black–Scholes model, which was first published in 1973. Options contracts were used for many centuries, however both trading activity and academic interest increased when, as from 1973, options were issued with standardized terms and traded through a guaranteed clearing house at the Chicago Board Options Exchange. Today many options are created in a standardized form and traded through clearing houses on regulated options exchanges, while other over-the-counter options are written as bilateral, customized contracts between a single buyer and seller, one or both of which may be a dealer or market-maker. Options are part of major category of financial instruments termed as derivative products or simply derivatives.

Types of Options:

- Call option: A call option is a contract giving the right to buy the shares. Call option that gives the right to buy in its contract gives the particulars of the name of the company whose shares are to be bought, the number of shares to be purchased, the purchase price or the exercise price or the strike price of the shares to be bought, the expiration date, the date on which the contract or the option expires (Gupta, 2005).

- Put option: It is a contract giving the right to sell the shares. Put option gives its owner the right to sell (or put) an asset or security to someone else. Put option contract comprises of the name of the company shares to be sold, the number of shares to be sold, the selling price or the striking price and the expiration date of the option.

The other two types are European style options and American style options. European style options can be used only on the maturity date of the option, also known as the expiry date. American style options can be exercised at any time before and on the expiry date.

Features of options:

- A fixed maturity date on which they expire (Expiry date).

- The price at which the option is exercised is called the exercise price or strike price.

- The person who writes the option and is the seller is denoted as the "option writer", and who holds the option and is the buyer, is called "option holder".

- The premium is the price paid for the option by the buyer to the seller.

- A clearing house is interposed between the seller and the buyer which guarantees performance of the contract.

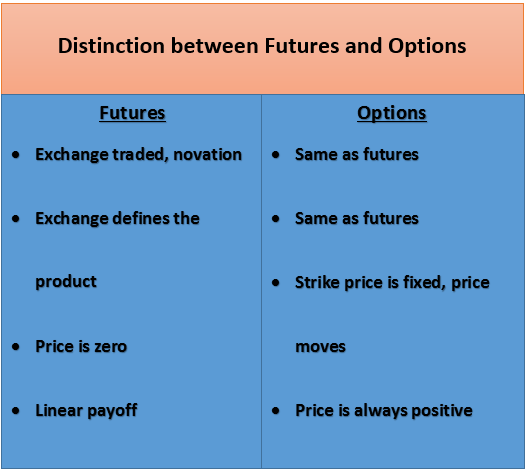

Futures:

In financial field, futures is a standardized contract between two parties to buy or sell a specified asset of standardized quantity and quality for a price agreed upon today with delivery and payment occurring at a specified future date, the delivery date, making it a derivative product. It can be said that it is traded on organized exchange. Futures work on the same principle as options, although the underlying security is different. Futures were conventionally used for purchasing the rights to buy or sell a commodity, but they are also used to purchase financial securities as well. The contracts are negotiated at a futures exchange, which acts as an intermediary between buyer and seller (Kevin, 2014). The party agreeing to buy the underlying asset in the future, the "buyer" of the contract, is called "long", and the party agreeing to sell the asset in the future, the "seller" of the contract, is said to be "short".

While the futures contract postulates a trade taking place in the future, the purpose of the futures exchange is to act as intermediary and mitigate the risk of default by either party in the intervening period. Due to this, the futures exchange requires both parties to put up an initial amount of cash (performance bond), the margin. Margins need to be proportionally maintained at all times during the life of the contract to support this mitigation because the price of the contract will vary in keeping with supply and demand and will change daily and thus one party or the other will supposedly be making or losing money.

To alleviate risk and the possibility of default by either party, the product is marked to market on a daily basis whereby the difference between the prior agreed-upon price and the actual daily futures price is settled on a daily basis. This is known as the variation margin where the futures exchange will draw money out of the losing party's margin account and put it into the other party's thus ensuring that the correct daily loss or profit is reflected in the respective account. If the margin account goes below a certain value set by the Exchange, then a margin call is made and the account owner must replenish the margin account. This process is known as "marking to market". Therefore on the delivery date, the amount exchanged is not the specified price on the contract but the spot value. Upon marketing the strike price is often reached and generate revenues for the "caller".

Types of future contract:

- Stock future trading

- Commodity future trading

- Index future trading

A closely associated contract is a forward contract. A forward is like a futures in that it identifies the exchange of goods for a specified price at a specified future date. However, a forward is not traded on an exchange and thus does not have the interim partial payments due to marking to market. Nor is the contract standardized, as on the exchange. Dissimilar to option, both parties of a futures contract must fulfil the contract on the delivery date. The seller delivers the underlying asset to the buyer, or, if it is a cash-settled futures contract, then cash is transferred from the futures trader who sustained a loss to the one who made a profit.

Swaps:

Swap means to exchange one for another. A swap is a derivative in which two counterparties agree to enter in to contractual agreement wherein they exchange cash flows of one party's financial instrument for those of the other party's financial instrument. Most swaps are traded over the counter (Gupta, 2005). Some are also traded as future exchange market.

Financial swap is specific funding technique which permits a borrower to access one market and then exchange the liability for another type of liability. In other words, swaps can be helpful to change the nature of liability accrued on particular instrument with the others. It means that swaps are not a funding instruments rather, just like a device to obtain the desired form of financing indirectly which otherwise might be inaccessible or too expensive (Gupta, 2005).

Swaps offer investors the opportunity to exchange the benefits of their securities with each other. For instance, one party may have a bond with a fixed interest rate, but is in a line of business where they have reason to prefer a variable interest rate. They may enter into a swap contract with another party in order to exchange interest rates. The benefits depend on the kind of financial instruments involved (Robert W. Kolb, 2014). For example, in the case of a swap involving two bonds, the benefits in question can be the periodic interest (coupon) payments related with such bonds. Precisely, two counterparties approve to exchange one stream of cash flows against another stream. These streams are known as the swap's legs. The swap agreement describes the dates when the cash flows are to be paid and the way they are accrued and calculated. Generally at the time when the contract is started, at least one of these series of cash flows is determined by an uncertain variable such as a floating interest rate, foreign exchange rate, equity price, or commodity price.

The cash flows are computed over a notional principal amount. Opposing to a future, a forward or an option, the notional amount is typically not exchanged between counterparties. Subsequently, swaps can be in cash or collateral. Swaps can be used to hedge certain risks such as interest rate risk, or to speculate on changes in the anticipated direction of underlying rates.

Swaps were first introduced to the public in 1981 when IBM and the World Bank entered into a swap contract. Presently, swaps are among the most heavily traded financial contracts around the globe (Gupta, 2005).

Features of swaps:

There are following features of swap (Gupta, 2005):

- Counter parties: All swaps are involved in exchange of a series of periodic payments between at least two parties.

- Facilitators: Swap agreements are arranged mostly through an intermediary which is usually a large financial institution/ bank having network of its operation in major cities. This institution is normally having contact with major international business firms who have direct link with other firms. These intermediaries play a significant role in bringing closure to the various parties of such deals. They will note down the requirement of the parties and try to match and fulfil these with other parties. Swap facilitators can be classified into two groups as Brokers and swap dealers.

Brokers: They functions as agents that identify and bring the counter parties on the table for the swap deal. The aim of broker is to initiate the counter parties to finalize the swap deal according to their respective requirement.

Swap dealers: They themselves become counter parties and take over the risk since the swap dealers are the part of the swap deals therefore they face two important problems. First how to price swap to provide for service. Second the swap dealers create a portfolio therefore the second problem is to manage this problem. - Cash flows: In the swap deal two different payment streams in terms of cash flows are estimated to have identical present values at the outset when discounted at the respective cost of funds in the relevant primary market.

- Documentations: Swap transactions may be setup with great speed since their documentations and formalities are generally much less in comparision to loan deals, it is an evaluation of various futures cash stream arisen out in various contract done in past. If the terms of different contracts suits the interested firm’s requirement, the deal will be enacted. Thus such deals are less complicated, less time consuming and simpler in terms of documentations and other formalities.

- Transaction costs: It has been observed that transaction costs are relatively low in swap transactions in comparison to loan agreements.

- Benefit to parties: Swap deals are needed as long as it is profitable to transform them. In other words, swap agreements is done only when the parties are benefited by such agreement otherwise such deals are not accepted.

- Termination: Since swap is an agreement between two parties therefore it cannot be terminated at one’s instance. The termination also requires to be accepted by counter parties.

- Default risk: Since most of the swap deals are bilateral agreements therefore the problem of potential default by either of the counter party exist hence making them more risky products in comparison to futures and options.

Types of Swaps Types of Swaps:

There are many types of swaps.

- Interest Rate Swap: This type of swap involves swapping only the interest related cash flows between the parties in the same currency. An interest rate swap is a contractual agreement between two counterparties to exchange cash flows on specific dates in the future. There are two types of legs (or series of cash flows). A fixed rate payer makes a series of fixed payments and at the outset of the swap, these cash flows are known. A floating rate payer makes a series of payments that depend on the future level of interest rates and at the outset of the swap, most or all of these cash flows are not known. Generally, a swap agreement specifies all of the conditions and definitions required to administer the swap including the notional principal amount, fixed coupon, accrual methods, day count methods, effective date, terminating date, cash flow frequency, compounding frequency, and basis for the floating index.

An interest rate swap can either be fixed for floating, or floating for. It can be believed that an interest rate swap is priced by first present valuing each leg of the swap and then aggregating the two results. - Credit Default Swap: Second category of swap is credit default swap which is a contract that provides protection against credit loss on an underlying reference entity as a result of a specific credit event. A credit event is generally a default or, possibly, a credit downgrade of the entity. The reference entity may be a name, a bond, a loan, a trade receivable or some other type of liability. The buyer of a default swap pays a premium to the writer or seller in exchange for right to receive a payment should a credit event occur. In essence, the buyer is purchasing insurance.

- Asset Swap: An asset swap is a blend of a defaultable bond with a fixed-for-floating interest rate swap that swaps the coupon of the bond into the cash flows of LIBOR plus a spread. In the case of a cross currency asset swap, the principal cash flow may also be swapped. In a typical asset swap, a dealer buys a bond from a customer at the market price and sells to the customer a floating rate note at par. The dealer then move in into a fixed-for-floating swap with another counterparty to counterbalance the floating rate obligation and the bond cash flows. For a premium bond, the dealer pays the client the difference of the bond price and its par. For a discount bond, the customer pays to the dealer the difference of the par and the bond price. In the swap with the counterparty, the dealer pays a fixed bond coupon and receives LIBOR and a spread. The spread can be determined from the cash that the dealer pays/receives and from the difference of the bond coupon and the par swap rate. When the bond redemption value is used for exchange of principal at maturity, the present value of the difference between the bond redemption value and its par value also contributes to the spread.

- Trigger Swap: A Trigger Swap is an interest rate swap in which payments are knocked out if the reference rate is beyond a given trigger rate. FINCAD provides analytics for two types of trigger swaps which are periodic and permanent. Periodic trigger swap refers to the exchange of payments depends on the reference rate set for that period. If the reference rate for a particular period is more than the trigger rate, the fixed and floating payments are knocked out. If the reference rate is below the trigger rate in a subsequent period, regular fixed and floating payments are made. For a permanent trigger swap, if the fixed and floating payments are knocked out for a particular period, then all successive payments are knocked out as well.

- Commodity Swap: A commodity swap is a kind of swap in which one of the payment streams for a commodity is fixed and the other is floating. Generally, only the payment streams, not the principal, are exchanged, although physical delivery is becoming increasingly common. Commodity swaps have been introduced and practiced since the mid-1970's and allow producers and customers to hedge commodity prices. Commonly, the consumer would be a fixed payer to hedge against rising input prices. The producer in this case pays floating thereby hedging against falls in the price of the commodity. If the floating-rate price of the commodity is higher than the fixed price, the difference is paid by the floating payer, and vice versa.

- Foreign-Exchange (FX) Swaps: An FX swap is where one leg's cash flows are paid in one currency, while the other leg's cash flows are paid in another currency. An FX swap can be either fixed for floating, floating for floating, or fixed for fixed. In order to price an FX swap, first each leg is present valued in its currency.

- Total Return Swap: A total return swap abbreviated as TRS is a two-sided financial contract in that one counterparty pays out the total return of a specified asset, including any interest payment and capital appreciation or depreciation and in return receives a regular fixed or floating cash flow. Typical reference assets of total return swaps are corporate bonds, loans and equities. A total return swap can be settled at the terminating date only or periodically.

It is documented in management literature that swaps with reference to financial market has two meanings. First, it is purchased and simultaneous forward sale or vice versa. Secondly, it is defined as the agreed exchange of future cash flow possibly, but not necessarily with spot exchange of cash flows. Financial swap is a specific funding technique which permits a borrower to access one market and then exchange the liability for another type of liability (Gupta, 2005).

Usage of derivatives:

Derivatives are used for the following:- Hedge or alleviate risk in the underlying, by entering into a derivative contract whose value moves in the opposite direction to their underlying position and cancels part or all of it out.

- Generate option ability where the value of the derivative is linked to a specific condition or event (e.g., the underlying reaching a specific price level)

- Obtain exposure to the underlying where it is not possible to trade in the underlying (e.g., weather derivatives).

- Provide leverage (or gearing), such that a small movement in the underlying value can cause a large difference in the value of the derivative.

- Speculate and generate a profit if the value of the underlying asset moves the way they expect (e.g. moves in a given direction, stays in or out of a specified range, reaches a certain level)

- Switch asset allocations between different asset classes without disturbing the underlying assets, as part of transition management

- Avoid paying taxes.

Advantages of Derivatives:

Derivatives are good investment mechanism that make investing and business practices more efficient and consistent. There are numerous reasons for investing in derivatives and it is advantageous:

Non-Binding Contracts: When investors buy a derivative on the open market, they are purchasing the right to exercise it. However, they have no obligation to actually exercise their option. Consequently, this gives them a lot of flexibility in executing their investment strategy.

Leverage Returns: Derivatives give investors the capability to make extreme returns that may not be possible with primary investment vehicles such as stocks and bonds. When person invest in stock, it could take seven years to double your money. With derivatives, it is possible to double his money in a week.

Advanced Investment Strategies: Financial engineering is an entire field based off of derivatives. They make it possible to create multifaceted investment strategies that investors can use to their advantage.

In derivatives market, people can manage huge transactions with small amounts and therefore it gives the benefit of leverage and hence even people who have less amount of money can enter into this market.

Derivatives is a great risk management tool and if applied carefully it can produce good results and benefit to its user.

Major drawbacks of financial derivatives:

The concept of derivatives is beneficial to investors. Nonetheless, irresponsible use by those in the financial industry can put investors in trouble. There are many disadvantages of financial derivatives.

Volatile Investments: Most derivatives are dealt on the open market. This is challenging for investors, because the security fluctuates in value. It is continually fluctuating hands and the party who created the derivative has no control over who owns it. In a private contract, each party can negotiate the terms depending on the other party’s position. When a derivative is sold on the open market, large positions may be purchased by investors who have a high likelihood to default on their investment. The other party cannot change the terms to respond to the additional risk, because they are transferred to the owner of the new derivative. Due to this volatility, it is possible for them to lose their entire value overnight.

Overpriced Options: Derivatives are also difficult to value because they are based off other securities. Therefore, it becomes much more difficult to accurately price a derivative based on that stock. Moreover, because the derivatives market is not as liquid as the stock market, and there are not as many “players” in the market to close them, there are much larger bid-ask spreads.

Time Restrictions: The main reason for derivatives to be risky for investors is that they have a specified contract life. After they expire, they become worthless. Potential for Scams: Many people do not understand the derivatives. Scam actors often use derivatives to build intricate schemes to take advantage of both unprofessional and professional investors. The most popular scheme is the Bernie Madoff ponzi scheme.

To summarize, financial derivative are securities which are associated with other securities, such as stocks or bonds. Their value is based off of the primary security they are linked to, and they are therefore not worth anything in and of themselves. Important aspect in the use of derivatives is the need for continuous monitoring and managing of the risks represented by the derivative instruments. There are different types of derivatives such as options, swaps and futures. Financial derivatives contracts are generally settled by net payments of cash. This often happens before maturity for exchange traded contracts such as commodity futures. Cash settlement is a logical consequence of the use of financial derivatives to trade risk independently of ownership of an underlying item. However, some financial derivative contracts, particularly involving foreign currency, are related with transactions in the primary item.